Prejudice is a great time saver. You can form opinions without having to get the facts.

—E.B. White

Today’s story is from Pierre O’Rourke.

For years I told anyone who would listen. My father was no father at all. The drinking, the carousing. The child support checks that never came. Mom and I moved away when I was nine. I would not see him again until I was a man.

“Maybe he did the best he could,” said my ever-forgiving mother, time and again. She and Dad kept in touch — some. She even sent him my report cards and letters. But I refused to write him a message or even acknowledge him.

But one night, one movie, one memory suddenly changed it all. I discovered that Dad was not so much a bad dad as a horribly haunted man.

Home from college, Mom and I plopped down, TV dinners in our laps. The movie: 1964’s “Black Like Me.” James Whitmore portrayed a white journalist going undercover as a black man. He traveled through the deep South. The insults. The denigration. It’s no easy film to watch—especially knowing it’s based on a true story.

In the midst of the movie I had a flashback. The recollection of a past time with Dad, a memory so bold it flooded my head. Flames, singing. Dad’s tattered and muddied shirt. The images stood sharp in my mind. I described the scene. “Do you remember, Mom?” I asked. She started to cry. I asked why … and found out.

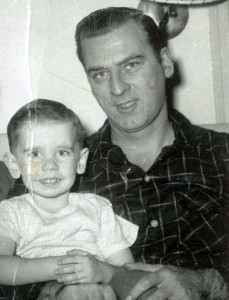

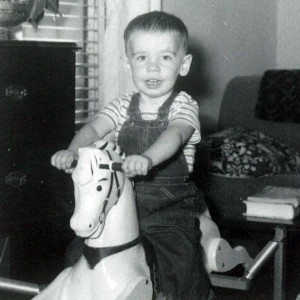

I was six. My father was home for the weekend — a rare occurrence, as Dad was often “working out of town,” or so I was told.

My father worked for Montgomery Ward, and dressed the part. A well starched shirt beneath a dark suit. A white folded handkerchief in his breast pocket, wing-tipped shoes. I used to earn coins for polishing those shoes, using tooth picks to clear the decorative holes.

Dad promised to take me “exploring” before dusk. At that time, towns surrounding the Chicago-area were separated by wooded areas. We set off for our adventure.

Childhood memories are often associated with things we already know. Bonfires meant camping. Crowds meant picnics. Loud singing meant a revival meeting. Hollering meant a carnival. Long strings meant kites in the sky.

That sunset I heard those promising sounds. I saw the sights, and a fire in the distance. I began to race down the hill toward the celebration — when my father grabbed me, and tackled me, with such force I lost my breath.

“We’re going to play Marines,” Dad whispered, his face close to mine, eyes wide. “Climb on my back.” I was “the wounded soldier,” he said. Dad was the brave rescuer.

“Hold onto my neck. Tuck your feet into my trouser pockets. Hold on tight.” It was “the sniper’s crawl,” Dad called it, and it was a blast.

Silently he inched up the hill with his “comrade” in tow. At last, we reached the crest. He pushed me into our tan and white Comet, and we drove faster than any time I can recall. Even the times he had been drunk.

That night Dad took me home and then vanished. It had happened before. This time, he was gone for three weeks. Mom admitted sadly that Dad was on a “drinking binge” again. That “something set him off.” I never asked. She never said what.

Now back to the movie. Steaming dinner tray on the coffee table. On the TV, James Whitmore disguised in dark skin. At my question, Mom sobbing on the couch at my side.

“We’d hoped you would never know what you had seen,” she said.

But now I did. It was in perfect focus. The crowd dressed in robes of red, black, and white—many with hats that seemed ‘funny.’ The fires were burning barrels and tall wooden crosses. The loud singing was chanting.

The hollering came from two black men as they were set ablaze. Another hung limp from a tree.

That night, I began to understand Dad. He was a haunted man. Mom told me that my father was torn. He knew he had done right in rushing me away, even though he wanted to try to save the men. Had I not been with him, he might have been crazy enough to try.

Mom told me that after Dad left home that night, he rushed to report what he’d seen to police.

He was jailed for three days and “injured due to resisting arrest and falling down the stairs,” (though there were no stairs at that jail, my mother said).

Once released, he headed for the bar. He attempted to drink away his guilt of failure.

Mom went on, and more memories returned. At Montgomery Wards, where Dad worked, I remembered helping him remove a “Whites Only” water fountain. I remembered him eliminating the dual restrooms. At the time, I merely saw it as getting rid of duplication.

I had no idea my father was taking a stand.

Dad was a functioning alcoholic, and a thorn in the side of his employer. But he was too good with employees, people, and the profit line to cast him aside. When Dad was away, I assumed he was drunk. Or that he didn’t want to spend time with us. That may have been true, in part.

But Mom now explained that Dad had marched in places such as Mississippi, Georgia, and Tennessee. He even had a hand in the Freedom Rides.

That night in front of the TV my heart opened to the fact that Stanley O’Rourke, my father, had some good in him. Perhaps quite a lot. That he might not have always done right, but he had done more right than many. He was brave.

That evening, I realized my dad had done things that make me proud.

The same year that I lost Mom, I made plans to go see my father in Kansas for the first time since 7th grade. We had begun phone chats on a monthly basis for the last three years. The trip was for his birthday, but the week prior he was rushed to the VA hospital where he drifted in and out of comas.

His drinking abuse had caught up with him. I spent the remaining 28 hours with him. He died in my arms as I reminded him that I understood he did the best that he could.

I told him he made me proud.

And now, I am telling you.

—Pierre

Pierre today with new family member, Gibbs, a 9-month old Australian Blue Cattle Herder

What a powerful story. As I read it, I had tears streaming down my face; for the man who tried to drink away the pain of being unable to help those men and knowing what might have been had he and his son been seen and for the little boy never knew the good in his father until he was a grown man. We all have prejudices that cause us to be blind. This story is a great reminder to me not to judge someone else unless you have walked a mile in their shoes.

Thank you for sharing your story.

Pierre can rip your heart out with his words. What talent he has with the pen.

I wish I could put on paper how I feel about my dad. I admire you for being able to do that. My dad and I have had a rough relationship at best. Even now as he is old and weak, I find it hard to know who he is, very complicated…..I can’t……..just not possible. Makes me sad.

K

This story just goes to show that everyone has good in them, not always “right in front of your face good”, but good none the less. 🙂

Thank you. It must have been extremely difficult to live that childhood. I know. I hope sharing this story made up for some of that. Hugs, Mary